Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction by Fergus M. Bordewich

Although the title of this book is somewhat misleading, as Ulysses S. Grant is something of a minor character, there is a lot of information about the early KKK, and anyone interested in American History will find this book a worthwhile read. Grant was a strong proponent of civil rights, but he’s not really the focus of the book. Bordewich does justice to Grant, detailing legislation he championed in support of civil rights, as well as the judges and cabinet members he appointed who helped make his vision a reality.

And it was a reality. Sort of. For a little while. The reader learns about many of the new elected officials, many newly emancipated, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, and the ways their activism pushed forward the civil rights agenda.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, there’s a backlash, and it is this that forms the bulk of this book. Alongside the stories of brave people who fought for equal rights are the stories of people who believed in both segregation and subjugation, and the violence they perpetrated in pursuit of their goals. There are numerous descriptions of lynchings, assaults, brutality, and cruelty as the KKK became more organized.

Readers will learn the many ways in which the KKK of the 1860s and 1870s was different from what we now think of the Klan, and may be surprised to find out the Klan was essentially dormant from the late 19th century until the early 1920s, at which point it was increasing immigration that provided the impetus for the resurrection of the Klan into what we know today.

Read-alikes:

The Wars of Reconstruction by Douglas R. Egerton

The Ordeal of the Reunion by Mark Wahlgren Summers

Ecstatic Nation by Brenda Wineapple

Mara Zonderman, Westhampton Free Library

Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan's Plot to Take Over America and the Woman who Stopped Them by Timothy Egan

In November 1925, Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon D.C Stephenson was sentenced for the murder of Madge Oberholtzer, whom he had raped and mutilated in March of the same year. Stephenson had gotten away with raping women for years before Oberholtzer was brave enough to tell her story on her deathbed. Her written testimony put him away. Fortunately, he was not just stopped from harming women, but from harming all minorities in Indiana.

Stephenson was a drifter who showed up in Indiana in 1923. He was a smooth talker and charmer. Hired by a KKK recruiter, he quickly rose up the ranks, expanding the Klan membership and infiltrating all avenues of Indiana politics and government. As he once said: “I am the law.” He was right. Police officers, judges, mayors, ministers – they were all under the thumb of Stephenson and the KKK. Though the KKK was supposedly a “brotherhood” of white supremacy (not necessarily against blacks, Jews, and Catholics, but just protecting their own race), Stephenson was a regular thug embezzling from the KKK, stealing from farmers, and ordering murders and lynchings.

When Stephenson was finally outed and convicted, many original KKKer’s were appalled at his behavior. Memberships quickly dwindled and their power waned.

This book was thoroughly researched by the author and is a relatively quick read. As non-fiction, we don’t get into anyone’s head, but we feel like we know the ‘characters.’ We easily hate Stephenson and his cronies and have great sympathy for Oberholtzer. However, this is hardly only Oberholtzer’s story. We are half-way through the book before we get to the night of the rape. The book also belongs to the newspaper editors, attorneys, and judges who were not swayed by Stephenson. Without them, Oberholtzer’s testimony would have never been made public at the trial.

Read-alikes:

The Second Coming of the KKK by Linda Gordon

Gangbuster by Alan Prendergast

Crooked by Nathan Masters

Lori Ludlow, Babylon Public Library

Boris Morros (rhymes with chorus) (1891-1963) was an American Communist Party member, Soviet agent, and eventually a FBI double agent.

Morros, born in St. Petersburg was a music child prodigy. As a child he attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory, studying under well known composers such as Anatoly Liadov and Nickolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Conservatory was one of the few institutions that enrolled Jews and provided housing permits so their families could legally live in the city. Later on, Morros was hired to organize, recruit, rehearse, and conduct the ensembles that performed for the tsar and his government.

Eventually Boris, along with his immediate family, made their way to the United States, arriving on Ellis Island in 1922. Morros relied on his music skills to gain work and eventually went to work for Adolph Zukor, owner of Paramount Pictures. Morros went on to become head of music at Paramount and eventually tried his hand at producing pictures (The Flying Deuces starring Laurel and Hardy).

In 1933, after meeting with an unsuspecting Boris, a Soviet spy wrote Moscow saying "During a conversation with Morros, I got the impression that he might be used to place our operatives in Paramount offices situated in every country and city, that he could be brilliantly put to use providing our workers with a cover." Over the next 14 years Boris or "FROST" (Soviet codename) did exactly that. In 1947, Morros became a counterspy and in addition to passing along FBI approved low-level secrets he also informed on the other spies in the spy ring. According to Gill, Boris "was ideologically uncommitted, constitutionally discreet, addicted to fame and money, and oblivious to the distinction between truth and fiction," traits that enabled him to survive purges, betrayals, and precarious Soviet politics."

This book is perfect for readers who like comprehensive, detailed oriented biographies, rich in history but that read like a thriller.

Gill did extensive research. Much of it came from readily available materials and well as 1930s and 1940s popular scholarly periodical materials, such as music, radio, theater, and film trade journals. He also conducted interviews with members of Boris's family. Unpublished as well as classified and declassified official sources proved to be very useful. One invaluable source was the archive that was collected by Alexander Vassiliev (former KGB) and eventually published in The Haunted Wood.

Read-alikes:

Symphony for the City of the Dead by M.T. Anderson

Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away by Anne Hagedorn

A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal by Ben Macintyre

My Ten Years as a Counter-Spy by Boris Morros

Movies:

Flying Deuces (Laurel & Hardy)

Second Chorus (Paulette Goddard & Fred Astaire)

Man on a String (Ernest Borgnine portrays Boris)

Sue Ketcham, Retired

Hankir presents an interesting survey of the use of eyeliner across time and geography. As a proud Lebanese-British journalist who has her feet planted in the cultures of both the Middle East and the West, Hankir shows how eyeliner plays important roles for both men and women in religious and cultural life.

The book is divided into ten chapters examining eyeliner in terms of different cultures, religions, and political expressions. For example, one chapter explains male beauty culture in central Africa, another examines eyeliner as a tool of political dissent for women in Iran, another explores eyeliner as a tool for expressing gender for drag performers, and another two chapters investigate the use of eyeliner for Japanese and Indian cultural performers. Each chapter gives a nice historical background of the area and the kind of eyeliner it uses, explanations of the use of that eyeliner, and plenty of interviews with people from that area explaining what it means to them. Hankir also provides a solid Works Cited section in the back of the book that allows for further exploration of the topics in each chapter - helpful as I found myself wanting to learn more about the different cultures that were introduced in each chapter.

The book itself is pretty accessible to the regular library reader. It seems solidly researched and definitely has a scholarly bent, but it is written in rather informal language (sometimes creating a jarring dissonance in her writing). One of the frustrating things about the book is that Hankir alternates between assuming the reader already knows about obscure topics (for example, providing words in Chinese characters without presenting the reading of those characters or using specific terms from different religions without explaining them clearly) and then overexplaining things that the general reader would already know. Also, the book seems to assume a more than basic knowledge of eyeliner and its use in Western culture, so if you do not wear makeup much yourself you will find yourself at a loss for understanding what a “flick” or “cateye” or “puppydog” or “graphic” eyeliner style looks like. It would have been good to have a chapter discussing the Western use of eyeliner as well - it would have provided a baseline for readers to understand the comparisons with the other cultures presented in the book. Each chapter also includes one black and white illustration representing the eyeliner style in the chapter, but it is very little compared to what is discussed. It would be easier to understand if more illustrations were provided.

Overall, I found this an enjoyable read. It was a tiny buffet of different cultures, religions, and people that made me curious to learn more. While the author’s strong political views can sometimes be off putting, I found myself reading eagerly and looking carefully at the women around me, wondering how their personal style of eyeliner was part of their cultural background and political views. I feel like a broad spectrum of readers would be interested in this book, including those who are interested in feminism and women’s culture as well as those who are interested in politics, religion, and physical culture.

Read-alikes:

Dress Like a Woman edited by Sarah Massey, Ashley Albert, and Emma Jacobs

Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close by Hannah Carlson

Unshaved by Breanne Fahs

All Made Up by Rae Nudson

Carolyn Brooks, The Smithtown Library - Commack Building

More memoir than history, Sweat: A History of Exercise by Bill Hayes takes us through a rambling journey of his search for information about exercise, and what seems to have become an obsessive interest in one particular work on the subject. The focus for much of the book is on Girolamo Mercuriale, a Renaissance Era physician who wrote and had illustrated a tome about exercise. While the work of Mercuriale was likely significant, it is not the first such work, and Hayes only scratches the surface of prior and later works on the subject.

After sessions in an archive with a librarian who begins to know him and anticipate his interests, he travels to both England and France to meet with scholars on Mercuriale and eventually is able to find a treasure trove of translated material. The materials that Hayes finds leads him further in his quest, and he eventually is able to view original copies of the drawings done for Mercuriale’s work.

Framed within the context of exploring Mercuriale’s work, and his own exploits in exercise, the reader learns of early Olympic games, boxing matches in Crete, and military training, which included women but only in Sparta. The narrative describes exercises that stem from Pehr Henrik Ling of Stockholm whose work led to the principles that guide modern PE classes. It also addresses the practice of Yoga and the changes it underwent in America, and the advent of television exercise programs as pioneered by Jack LaLanne. This era also saw the rise of body building as exemplified by Arnold Schwarzenegger, martial arts by Bruce Lee, and other sports such as swimming and running by celebrity athletes. Title IX opened the door for women and girls to participate in sports in a way previously impossible. Hayes’ description of these changes is clear although brief.

His hunt for original works will appeal to history buffs who will be captivated by the idea of looking at books buried deep in archives of prestigious libraries and even a castle on an isolated island in Italy. While Hayes likely compiled an incredible trove of information and experience in his multi-year quest, he leaves the reader feeling undereducated on the subject.

There is too much focus on one author, not enough meat for comparison with those who came before, and a mere glance at modern trends. The athleticism of the author could be a means for connectivity for athletes or exercise aficionados. Hayes has done or tried it all - running, swimming, gym workouts with weight lifting, yoga. He seems to show a great deal of reverence for Mercuriale but has no problem mocking practices such as sweat collection for skin care, which we now know to be useless and really just gross.

This book would be a good beach read for non-fiction lovers. Although catalogued as a history, it is more a memoir of Hayes’ studies of exercise, both physical and academic. Readers who enjoy memoirs, exercise, and in-depth research will enjoy this book.

Read-alikes:

Making the American Body by Jonathan Black

Let's Get Physical by Danielle Friedman

Ultimate Fitness by Gina Bari Kolata

Embrace the Suck by Stephen Madden

Fit Nation by Natalia Mehlman Petrzela

Ellen Covino, Sayville Public Library

Names of New York: Discovering the City's Past, Present, and Future Through It's Place-Names by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Ever wonder how the streets, towns, buildings, etc. of New York City came to be named? From the native Lenape to the Dutch settlers and beyond, Jelly-Schapiro tells the history of New York City through those who lived here, settled here, and have made the City their home for over 300 years.

The beginning of the book is about the Lenape meeting the Dutch settlers and the language barriers that ensued. From that, the Dutch began to rename things in their own language, which continued throughout history as each new group settled in the city. As we get closer to present times, we learn more about the boroughs as the City grew and how subway stations, neighborhoods, and waterways get named based on cultural significance and historical importance.

The book is short but densely packed with information. A lot of the beginning is repetitive going over the renaming of the same areas as new settlers came in quick succession. Around the midway point, it gets more interesting as the reader more easily recognizes the areas being discussed and can relate more to the history. Interesting chapters include a section on Hart Island, where inmates from Riker's Island have dug graves for the city's largest potter's field, as well as a chapter about the time when the city began renaming streets every time someone put in a request causing all sorts of confusion for locals, local businesses, and visitors alike since maps couldn't keep up with the constant changes.

Overall this was an interesting read, but unless you're a history buff, it's slow going for half of the book. Due to this, I wouldn't give this book to the general reader. It's better suited to readers looking for a history of New York City or those who like to know why streets and towns got their names.

Read-alikes:

City Grid: How New York Became New York by Gerard T. Koeppel

Broadway: A History of New York City in Thirteen Miles by Fran Leadon

Gotham Unbound by Theodore Steinberg

Azuree Agnello, West Babylon Public Library

This well-researched, in depth overview of the 1990s is an eclectic dive into the American grunge era of pop culture, entertainment, sexism, racism and politics. Within the first footnote, the author acknowledges potential biases - “Transparency requires me to admit a few things here, if only to aid those primarily reading this book in order to locate its biases: I was born in 1972. I’m a white heterosexual cis male. I was economically upper-lower-class in 1990, middle-middle-class in 1999, and am lower-upper-class as I type this sentence.”

Klosterman goes on to cover many newsworthy topics - Bill Clinton’s impeachment, OJ Simpson’s murder trial, LAPD brutally beating Rodney King, Anita Hill’s testimony; the rise in commercial popularity of different music genres - Alternative and Gangsta Rap; notable sports moments like the home run record chasing race between two players that were using performance enhancement drugs; the Titanic movie and that song we still can’t get out of our heads, and so on.

Considering the vast amount of information that is covered in this book, the pacing is definitely adequate. The Nineties will appeal to those that lived through them, heard stories about being a teenager back then from their very cool 40-something aunt, or anyone with a general interest in US history.

Read-alikes:

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History by Kurt Andersen

Rock Me on the Water: 1974 by Ronald Brownstein

Music is History by Questlove

Jessicca Weber, The Smithtown Library - Kings Park Building

The Core of an Onion by NY Times Bestselling author Mark Kurlansky discusses the origin and history of the beloved and humble bulb. As Julia Child once said, “It is hard to imagine a civilization without onions." Onions have been around since the beginning of time. They have been found in the tombs of Egyptian mummies, and Herodotus, the famous Greek historian, claimed that during the construction of the pyramids, the workers were fed on large quantities of onions, garlic, and radishes.

This book sites dozens of examples of the importance and value of onions. Onions are worthy subjects of art, and many artists including, Renoir, Cezanne, and Van Gogh immortalized the bulb in still life drawings and paintings. Onion’s popularity also shows up in literature and poetry. In Lewis Carroll’s Adventures of Alice in Wonderland, the Queen of Hearts threatens the Seven of Spade for bringing the chef a tulip instead of an onion. According to many botanists and archeologists, it is believed that onions originated in central Asia over 5000 years ago and it is thought that onions were discovered and eaten wild long before farming or writing was invented. The onion has been praised for medicinal purposes and at one time was popular in some cultures as an aphrodisiac. Hopefully the user cooked the onions first.

I could go on and on and by now you are probably asking, why do onions make us cry. Contrary to popular belief, it is not the odor of the onion that causes one to cry but a vapor that is released when the onion is cut. The toxic vapor transforms into an irritant when it comes into contact with the liquid in your eyes and causes the eye to tear. This book goes into several techniques to prevent that from happening, but you will have to read it for yourself to find out.

This book could have easily been called, everything you wanted to know about onions but were afraid to ask. I enjoyed learning about the many cultivars of onions. It is believed there are well over 600 types with more on the horizon. Each page of this slim book contained interesting tidbits and facts about this commonly used food.

This book is for anyone who loves to eat, cook, or garden. The pace is fast and can easily be read or listened to in a weekend. The book includes a 100 historical recipes that will make you long for a perfect bowl of onion soup.

Read-alikes:

Sweet Land of Liberty: A History of America in 11 Pies by Rossi Anastopoulo

A Short History of Spaghetti with Tomato Sauce by Massimo Montanari

The Secret History of Food by Matt Siegel

Karen McHugh, Harborfields Public Library

Mundy, author of the bestselling Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II (2017), returns with another work of espionage history centering women. Intrigued by CIA history while researching her earlier book, Mundy interviewed current and former CIA officers in order to tell the story of the CIA from its inception during World War II through the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011.

The Sisterhood reads like any well-written and thoroughly researched work of history, replete with anecdotes, quotes, major and minor events, and biographical sketches. For this reason, I would recommend the book to any reader of history. Increasing its appeal is its novelistic structure: exposition, increased conflict, climax, and resolution.

The book begins with an exposition of how women gradually increased their presence and influence at the CIA from the 1940s to the 1980s. During this period, the CIA had a very macho culture, what the author calls the “Old Boys’ Club.” Women faced sexual harassment and sexist comments and were subjected to a double-standard. They were also denied promotions and were excluded from career-track positions. They did important work, but men received the credit. This was infuriating to read, but that indignation propelled me through the book.

This first part of The Sisterhood especially focuses on female clandestine officers. Originally, women were excluded from receiving spy training at “The Farm,” the intense training camp where CIA agents are equipped for overseas service. However, highly talented women refused to give up on their dreams of becoming Case Officers. They persisted and excelled as Case Officers during the Cold War, obtaining important intelligence. Interestingly, their sex gave them multiple advantages, such as their ability to fly under the radar of the enemy and to use their emotional intelligence to win trust.

Moving into the 1990s, the book shifts settings from overseas to Headquarters. During this time, women at the CIA landed numerous victories. For example, a small team of women tirelessly investigated and exposed Aldrich Ames, a CIA officer and a Russian mole, who was arrested in 1994. Women also won legal cases against the CIA, including one in which officers’ wives, most of whom had performed critical unpaid intelligence work, were able to receive part of their ex-husbands’ pensions after divorce.

During this second part of the book, Mundy shifts the focus off clandestine officers and onto the female analysts who worked at CIA Headquarters. She highlights their brilliance and expertise. This section of the book builds significant tension and conflict as we learn about the founding of Alec Station, the Bin Laden Issue Station in the basement of Headquarters. These genius women were experts on terrorism, Al Qaeda, and bin Laden, amassing an impressive wealth of intelligence on the growth of Al Qaeda in the 90s and submitting countless papers and reports to their superiors regarding the growing threat. They even alerted their superiors to multiple opportunities to kill bin Laden. Unfortunately, their warnings went unheeded for most of the decade. Mundy offers multiple reasons why their warnings were ignored, but the fact that the department was staffed primarily by women was undoubtedly part of the reason why they were not taken seriously.

This drumbeat of impending doom left me with a visceral sickness as I recognized that the analysts would not stop bin Laden in time to save thousands of lives. The tension peaks as Mundy recounts the events of 9/11 and the intense guilt, fear, and drive felt by the female officers in its aftermath. As a reader, it was fascinating to watch the analysts and clandestine officers join forces in the singular effort to fight terrorism and catch bin Laden. Because the women of Alec Station had been tracking bin Laden for years, their expertise suddenly became desperately needed and sought after. Women played an essential role in the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011, and it was gratifying to see these women holding significant leadership positions. However, even well into the 2010s, female officers still faced prejudice, sexism, and a double-standard.

Like any good story, The Sisterhood has several main characters, and the book wraps up by telling us what became of women like Lisa Manfull Harper, Heidi August, Cindy Storer, and Gina Bennett, whose careers we follow from the beginning of the book. These biographical details are crucial for maintaining reader interest throughout this 400+ page book. Additionally, several exciting events keep the pages turning. The 1985 plane hijacking in Malta, for example, becomes a pivotal moment for Heidi August, compelling her to fight terrorism for the remainder of her career. Unfortunately, the book often gets stuck in a slog of confusing Headquarters politics and office drama. It was difficult at times for me to keep track of the various departments, positions, career changes, minor characters, and overlapping timelines. This is not a James Bond novel, and I would not recommend it to readers looking for that type of book.

Instead, I would recommend this book to anyone, male or female, who is interested in international relations, American foreign policy, the CIA, Washington culture, and counterterrorism. I would also recommend this book to readers who enjoy empowering stories of brilliant women defying sexist power structures. It is an inspiring, but heavy read.

Read-alikes:

Circle of Treason by Sandra Grimes and Jeanne Vertefeuille

Wise Gals by Nathalia Holt

In True Face by Jonna Mendez

Emma Yohannan, Central Islip Public Library

by Sarah Ogilvie

I never thought about how new dictionaries become established, especially one that would become the first dictionary of the English language that aimed to start with the Anglo Saxons and describe the language, word origins, and their usage.

Sarah Ogilvie has written a book about just that. Ms. Ogilvie is a linguist, lexicographer, computer scientist, writer, professor, and former editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. Dr. Ogilvie is currently a member of the Department of Linguistics, Philology & Phonetics at Clarendon Institute, University of Oxford.

Her book is filled with the stories about the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and the brilliant, quirky, dedicated volunteers who toiled for many years to compile the dictionary.

The OED was first proposed by members of the London Philological Society in 1857. Ads were published in newspapers and literary publications asking for volunteers to read books and send in slips that specify a word and quote of its usage in the book. Many people responded by sending in hundreds of thousands of slips over the 70 years it took to complete the OED. In 1879 Oxford agreed to publish the work. It’s first edition came out on January 29, 1884. Two of its best-known editors were Frederick Furnivall and the Scottish lexicographer, James Murry. There have been several updated editions over the years along with a CD-ROM version in 1987 and the first online edition in 2000.

Who were these volunteers? According to Dr. Ogilvie’s professionally researched and well written book, they were, average people, language specialists, alcoholics, architects, inventors, linguists, philologists, kleptomaniacs, scientists, medical doctors, a murderer, a cannibal, suffragists, and the daughter of Karl Marx, along with many, many more. They came from all over the world. The OED has been called the “Wikipedia of its time.”

The creation of this historical publication is extremely interesting and reads like a mystery, but it might not be for everyone at 384 pages. Anyone who loves words and language and stories about eccentric, remarkable people should give it a try.

Read-alikes:

The Dictionary Wars by Peter Martin

The Professor and the Madman by Simon Winchester

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Jo-Ann Carhart, East Islip Public Library

Throughout history, there are many peoples or past Empires and Kingdoms who, when mentioned, conjure up clear images in the minds of people today. The Romans, the Mongols, the Pilgrims, or the Aztecs; whenever groups like these are spoken of, most of us will have similar ideas of who and what they were in our head. Many of us will (hopefully) recognize that the images in our heads don’t perfectly represent who these people were, but usually the disparity isn’t too great. However, movies and television, as well as the simple passage of time, warp our understanding of history, leading us to misconceptions or overgeneralizations. The task of good historical non-fiction books is often to sift fact from fiction and correct our preconceived notions. Perhaps no people in all of history however, have a wider difference in their public perception versus their lived reality, than the people commonly referred to as the Vikings.

From the horned helmets that were invented in the 19th century for a production of a Germanic opera, to the idea that they were wild-haired savages eating magic mushrooms to begin blood-lusted rampages through Christian Europe; almost everything the common person pictures when thinking of the Vikings is either misguided or a complete fabrication. For his newest book, Children of Ash & Elm: A History of the Vikings, archaeologist Neil Price meticulously deconstructs the web of lies and confusion that surround these extraordinary people.

For many, reading historical works is an attempt to fill in the gaps of our knowledge, a way to bring the past into living color. With a people like the Vikings, Price’s task is less about adding depth to what the average reader knows, but more akin to a sculptor carving away at a block of stone to reveal the truth of the Vikings, hidden beneath our preconceptions. Price spends the entire first third of the book challenging the reader to center the Vikings in their own narrative, even using multiple pages to discuss whether ‘Vikings’ is even an appropriate word for the people of Scandinavia in this time period. Too often, the Vikings are portrayed as a hitherto unknown people, exploding into the history of Europe in the period after the Roman Empire falls and before the European Kingdoms of France, England, or the Holy Roman Empire can take root. Instead, like the title suggests, Children of Ash & Elm places them firmly in their own world first, before seeing how their interactions with the rest of Europe and Asia play out. Or as Price puts it in his introduction; “What, for some, is ‘background’, building up to what the Vikings accomplished out in the world, is here the point itself.”

These parts form the strongest sections of the book, where Price uses archaeological evidence as well as the few surviving contemporary accounts, to give the reader an idea of who the Vikings were. Not just how they dressed or built their homes, but what motivated them to dress or build that way, how the natural world around them shaped their beliefs, and most importantly, how the Vikings viewed themselves as individuals and as a community. Only when Price has sufficiently described these people, does he go into the more traditional history; the monastery raids, the invasions of England and France, as well as the settlement of Iceland and North America. Yet he routinely goes to great pains to remind the reader that we should not view these events simply as dates with lines on a map. He wants the reader to understand what is motivating these people on these extraordinary journeys. Many of the stories Price highlights in these sections survive as mere fragments of the incredible and mysterious lives these people led. Warriors who traveled from their homes in Sweden to the far East of Baghdad, before settling somewhere in England. A Queen from Iceland that possibly visited North America before her meeting with the Pope. Or even the regular farmers who erected massive stones carved in intricate runes, to honor their families, and leave behind a legacy for their descendants.

Children of Ash & Elm is an incredibly rich work, but that richness also comes with density. Those not used to reading academic historical non-fiction may be daunted both by the size, clocking in at just over 600 pages, and by the writing style standard to this level of research. The structure of the book could also confuse those who have no understanding of European history in this period (roughly covering the years 600 - 1200) as Price bounces around in both time and space, rather than following any sort of linear timeline as a more traditional history book might. Anyone with the faintest interest in the Vikings should read Children of Ash & Elm, those without that interest may lose steam after hearing about yet another burial mound and what its findings mean for historians and archaeologists. For those who crave richness and complexity when reading, Price’s newest book is an excellent work about one of history’s most misrepresented and misunderstood people.

Read-alikes:

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard

Northmen: The Viking Saga, AD 793-1241 by John Haywood

River Kings by Cat Jarman

Connor McCormack, Northport-East Northport Public Library

The Object at Hand: Intriguing and Inspiring Stories from the Smithsonian Collections by Beth Py-Lieberman

The Object at Hand gives a behind-the-scenes look at many items in the Smithsonian collections. The items are grouped into 13 different themes such as audacity, utopia, haunting, lost, optimism, rhythm, and revealing. This gives an emotional dimension to the objects, how they relate to each other, and how they fit into the larger American story. Items highlighted in the book include Thomas Jefferson’s Bible, John Lennon’s Stamp Collection, Alan Shepard’s Spacesuit, and the Hope Diamond.

This was an interesting book. Over 100 objects are highlighted in 250 pages. Each item has 1-2 pages written about them starting with which museum the object could be found in, giving a brief description, history of the person/group it belongs to, and wraps in how the thematic chapter word relates to the object. I found the book interesting, but wished there were pictures of each object. I spent a lot of time using the Smithsonian Institution website to search the object to visually see what was being talked about. Unlike many Smithsonian books, this one is also in black and white, which loses some of the connection that would be found in colored pictures. I would recommend this book to anyone interested in little doses of history and would like a taste of what will be found on a trip to Washington D.C.

Read-alikes:

All the Beauty in the World by Patrick Bringley

Rendez-vous with Art by Philippe de Montebello

The Boston Raphael by Belinda Rathbone

Nanci Helmle, The Smithtown Library - Commack Building

Richard Snow brings a factual account on how one of the greatest amusement parks came to be. This title discusses Walt Disney’s early life, building up to his ideas and reasons for wanting to create such a place. The author shares the challenges and setbacks in developing Disneyland, including finding a location, obtaining funding, and working with many who had limited knowledge of a skill while learning on the job. After building a miniature railroad of his own in his backyard, Walt was inspired to build something bigger so that the world can enjoy a clean park with an emphasis on having a happy staff. He decided to hire data analysts who examined the best developing area in California and bought property in Anaheim for $4,600 an acre. Walt’s brother, Roy Disney, took on the business end for Walt, managing to get ABC network to invest a half a million dollars in Disneyland. The author writes about the important figures who aided in the building and construction of Disneyland including Vice President C.V. Wood, engineer of the Mark Twain Joe Fowler, landscaping company the Evans Brothers, Arrow Development Co. who built Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, the Tea Cups, and Harriet Burns, the first woman to be hired by Disney, who worked on props and miniature models.

When Disneyland finally opens, a televised show airs with host Art Linkletter announcing the parade, interviewing guests and providing a dedication to each land in the park. The show was a success, but on the inside of the park, it was a mess. Thousands of people were entering who really weren’t supposed to be there, causing long lines for attractions and bathrooms. They ran out of food, people left with paint stains on their clothing due to last minute paint jobs and the rides did not run smoothly. The press had a field day writing up all they saw on opening day, but it did not deter people from coming the next day. Eventually, with the right equipment and expertise, rides began operating correctly and soon more attractions were added. This non-fiction piece ends with Walt’s death from lung cancer. The light in Disney’s firehouse apartment burns all night long every night of the year. On the window are names that helped birth Disneyland along with phrases said by these dreamers. For a historical non-fiction story, the author clearly organizes the events chronologically in short chapters, appealing to any ride enthusiast and to anyone who wants to learn more about Disney’s dream. I felt the concise writing made this book appealing to those who enjoy less detail in informational pieces and the people introduced in each chapter made it a memorable story of the vision that came true.

Read-alikes:

Architects of an American Landscape by Hugh Howard

The Disney Animation Renaissance by Mary Lescher

Three Years in Wonderland by Todd James Pierce

Liana Coletti, West Islip Public Library

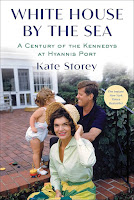

The Kennedys are the closest thing to a royal family that America has ever seen. The Big House (as it was affectionately called) is the family home that provided stability for every event and emotion that the Kennedy family endured over the years—everything from over-the-top exhilaration to the darkest depths of despair.

The year is 1928. A family of “new-money Irish Catholics” move to a tight-knit community of wealthy, conservative residents. The residents of Hyannis Port did not flaunt their wealth, so one couldn’t help but notice when Joseph Kennedy arrived in a flashy, chauffeur-driven car. Though the Kennedy family was not readily accepted, neighbors did express that they felt that someone in the family was likely to end up being president of the United States—the family was that vivacious.

Joe Sr. came from a political family in the Boston area, so it was not surprising that he had political aspirations for his offspring, particularly his eldest son Joe Jr. The family was devastated when Joe Jr. was killed on a mission in Europe during WWII. The family rallied, as their philosophy was to keep moving forward, even under dire circumstances. John, the second eldest who also served during the war, was deemed a hero when he saved his PT crew after an attack in the Pacific. Upon his return home, it was understood that John would carry the torch that was originally meant for his older brother..

The Big House is portrayed as a haven, a gathering place, the backdrop for every Kennedy generation since the 1920s, through to this day. Author Kate Storey draws on hundreds of conversations with family members, friends, the Big House staff; oral histories, newspapers, and books in the writing of this comprehensive, easy-to-read history of a house that became an actual member of the Kennedy family. The happier times over the years are thoroughly examined, and a loving and supportive family unit is portrayed. And then there were the low points: the death of Joe Jr; the medical procedure that left daughter Rosemary permanently disabled; the assassination of President Kennedy; the assassination of presidential-hopeful Robert Kennedy; the incident at Chappaquiddick; the tragic plane crash that took the lives of John Jr. and his wife Carolyn. All of these milestones are covered extensively, and the book breathes life into the saga of a single family and the home they shared.

Read-alikes:

Astor: The Rise and Fall of an American Fortune by Anderson Cooper

Forever Young: My Friendship with John F. Kennedy, Jr. by William Noonan

Deborah Formosa, Northport-East Northport Public Library